Eminences, Excellencies, Magnificentia, Spectabilis, dear colleagues, esteemed guests.

It is the time of Lent. According to an ancient tradition, altar pictures and crosses are covered up in churches. The abandoned throne of St Peter and the veil of mystery over the future of the church lend the present Lenten experience of God’s silence a strange aura of urgency.

Many pictures that we have grown too accustomed to are covered up. Confronted by the dark canvas we are able to recall what we used to see and what is now concealed. But we can also turn that concealing veil into a projection screen for our fantasies, our wishes or our fears. We have heard repeatedly that religion is either a memory of what was and is no longer or a projectiono of our illusions and fantasies. And there certainly exist forms of religion that this criticism rightly refers to.

During Lent the church interior looks different from what we are used to. God is not limited to what we are accustomed to. God also comes to us in otherness.

Maybe it is precisely and above all in difference that God comes. I would put it even more strongly: God is the otherness of reality. Religion is discernment of that otherness, of what is distinct and new.

One of the attempts to interpret the concept of religio derives the word from re-legere: reading anew. Reading anew and in a new way, reaching a deeper understanding of the text. We hear a lot nowadays about “new evangelization”. Ought it not be schooling in the art of reading the book of reality – history as it happens – in a different way: more attentively and in greater depth?

The pictures and crosses in churches are covered up until Good Friday when we recall when God was most radically hidden, God’s hiddenness, as expressed in Jesus’ cry on the cross: My God why have you forsaken me?

That sentence can also be translated as: My God, for what purpose have you forsaken me? What is the meaning of it? At that moment the sentence is no longer a cry of despair and resignation, but a prayer in the form of an urgent question. Maybe our profoundest prayers could take the form of questions. Maybe our profoundest questions could become prayers. There are questions that are so momentous that it is a pity to spoil them with answers.

Maybe in the history of theology we gave too many hasty answers where there was time and space more for questions and contemplation. Maybe the time has come for us to turn our answers back into questions again and dwell with questions in the house of God’s silence and hiddenness.

In many of its translations into other languages my book “Vicino ai lontani” bears the title “Patience with God”. It chief message is this: There are moments in the history of humanity, as well as in the history of the church and in our own lives, when we are confronted more than at other times with God’s hiddenness, God’s silence. Silence is not the absence of communication. Silence is communication that can have many meanings and which is therefore subject to many different interpretations.

Atheism interprets God’s silence by the sentence “God doesn’t exist”, or “God is dead”. The traditionalists do not hear the gentle music of God’s silence but instead go on repeating the old formulae. Emotional piety drowns out God’s silence with its ardent alleluias. Agnostics shrug their shoulders uneasily. But a mature faith is capable of enduring God’s silence and hiddenness. Faith as I understand it is the courage to enter the cloud of Mystery and live with mystery. For that we need faith, hope and love.

I am frequently asked how to explain the fact that my books have been translated in recent years into many languages and have been read attentively in many countries on several continents, including by people who do not regard themselves as religious believers. I cannot sidestep the question by simply referring to my readers and critics. Many are surprised that this theology come from a country that is regarded as the most atheistic in Europe, if not in the entire world. Is it possible that something good in the sphere of religion could originate in the Czech lands?

Perhaps I could answer the question by referring to the roots of my theology. And I am not referring in this respect to my philosophical, theological and spiritual sources of inspiration, ranging from apophatic theology, mysticism, Kierkegaard, and the theology and philosophy of dialogue, to certain contemporary authors.

My theology grows out of the painful experience of Christians in my home country, which was subjected to harsher persecution during the decades of the communist regime than any of the surrounding countries. My teachers of faith and theology were professors of theology who had spent fifteen years of their lives in the grim conditions of communist prisons, concentration camps and uranium mines. For some of them something remarkable happened to them there. They shared their ordeal not only with other priests but also with Christians of other persuasions and with non-Christians. After their release they first received news of the recently concluded Second Vatican Council and its reforms.

Their profound affirmation of the Council’s message and its appeal for ecumenical dialogue, as well as dialogue with other religions and with the contemporary world, grew precisely out of their dearly bought experiences. They wholeheartedly welcomed the Council’s decision to abandon various expressions of triumphalism and become a servant church in solidarity with the oppressed and the poor.

My professor of philosophy was the Czech philosopher Jan Patočka, a pupil of Edmund Husserl. Together with my friend Václav Havel he became the first chairperson of the Charter 77 human rights campaign – and that commitment cost him his life. Each of those teachers were for me – in the words of Master Eckhart – not just a “Lesemeister”, but also a “Lebensmeister”, not just a teacher of theory but also of practical morality. That is an onerous legacy – and I feel all the time how enormously inadequate I am to fulfil that task, to be faithful to that legacy and cultivate it in new conditions.

My theology also grows out of my own life experience. For almost twenty years after graduating from university I was not allowed to teach publicly or to publish. I was not allowed to travel to the West. For eleven years after my clandestine ordination I was not allowed to exercise my priestly ministry in public – it was impossible for me even to inform my mother about my ordination. I spent the first ten years after the fall of the communist regime chiefly on study trips and lecture tours, visiting many countries and every continent of our planet. Only after I celebrated my fiftieth birthday did I realise that the blossoms of my tree had fallen and it was time to bring forth fruit. Every year since then I have withdrawn for five weeks to the total solitude and quiet of a hermitage near a contemplative monastery, where all my books have been written.

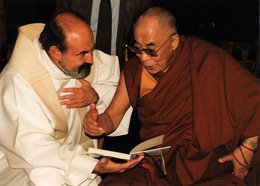

During the past twenty years since the fall of the communist regime I have devoted myself chiefly to dialogue with thinkers and also ordinary believers, not only of other Christian churches but also other religions. My thinking and spirituality is inconceivable without inspiration from sources within contemporary protestant theology, from the spirituality of the eastern Orthodox churches, without Jewish and Christian reflection on the Holocaust, without the experience and practice of Zen meditation as transmitted to me by Jesuits from Japan, or without conversations with Islamic scholars. And yet I have never advocated shallow syncretism or relativism. On the contrary, I have warned against them. I have striven to cultivate a philosophy and theology of dialogue that respects the other’s difference and tries to perceive that difference not necessarily as a threat, but rather as a step in the direction of a certain complementarity. That complementarity can only fully emerge, however, when God, who is the “complexio oppositorum”, will – in the words of the Bible – be “all in all”.

I try to contribute to the philosophy of dialogue with my theory of “negative eschatology” and “eschatological difference”, difference between the present state of the church and theology on the one hand, and that full perception of the truth, which is the subject of the eschatological promise.

I have striven to study with an open mind the works of critics of religion – particularly the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche – and perceive them as support for efforts to cleanse religion of its immature forms. I believe that my theological hypothesis about “ressurectio continua” – which seeks to interpret the central mystery of Christian faith as a process that continues in the lives of people seeking the truth – may be a contribution towards spiritual theology and pastoral practice.

In the recent period I have been addressing the idea of “the afternoon of Christian history”. C. G. Jung compared human life to a day. The morning of life is a time for building the outward structure of one’s life. Then comes the “noonday crisis”. In the second part of life, Jung maintained, people should not simple improve on those outward structures, but they should seek their inner depths and develop the spiritual dimension of their lives.

It strikes me that the Catholic Church in our part of the world (and, in a sense, European culture as a whole) currently finds itself in that “noonday crisis”, when it is in danger of “accedia” – decline, torpor, what these days we call depression or “burn-out syndrome”. The “morning of Christian history” was when important institutional and doctrinal structures were constructed. Now we are witness to controversy within the church between those who want to preserve those structures in their present form at all costs, and those who want to radically change them, come what may. I fear that both sides risk overlooking a third option. This consists of not concentrating so much on the outward structure, but of “a journey into the depths” – striving for radical spiritual and intellectual renewal.

I do not mean by that journey into the depths some “escape into a garden of private piety”. Today’s church should draw inspiration from one of its most valuable past forms – the idea of the mediaeval university. The university was perceived as a community of teachers and pupils, a community of life, study and prayer. Truth was to be sought by means of free discussion – where everything could be propounded as a “questio disputata”. Nevertheless a crucial principle was the linkage between intellectual activity and the spiritual component of life: Contemplata alliis tradere. If my book can help make a small contribution towards the fulfilment of my dream of the church of the future as a community of life, study and prayer, I will be very grateful to God. At present I am very grateful to those who have assisted its publication, particularly the Libreria Editrice Vaticana and the translator Mrs Alessandra Mura – and I will be grateful to all those who read my book with kindly attention.