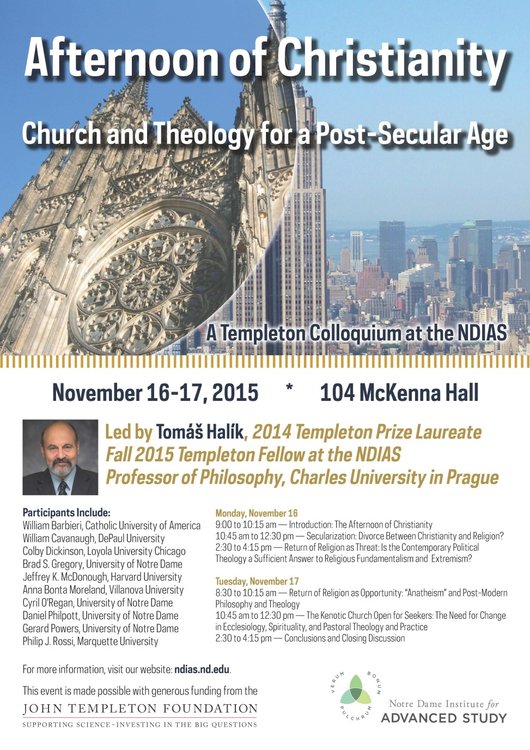

A Templeton Colloquium at the NDIAS (November 15-17, 2015)

By Msgr. Dr. Tomas Halik, 2014 Templeton Prize Laureate

An Introductory Essay for Participants and Discussants

Carl Gustav Jung used the metaphor of the day to describe the development of the human personality in the course of a lifetime. The morning of life (youth) is a time for building the external structures of personality. During the midpoint of life a noonday crisis emerges. This crisis can take the form of shock or loss of previous certainties (such as a crisis in one’s marriage or occupation, financial or health problems, etc.) or exhaustion and a general malaise (a burn-out syndrome). The noontime crisis is also an opportunity for a major change, a chance to tackle the tasks of life’s afternoon, and to move from outward considerations to the depths.

Jung’s metaphor of the day can be applied to the history of Christianity. Christianity’s long history up to the beginning of modernity represented its morning – a time for building institutions and doctrinal structures. Then, in the West, a noonday crisis occurred as Christianity clashed with modernity, with secularization and a popular belief in “the death of God” characteristic of this ongoing phase. This crisis will continue until such a time as it will be understood as an opportunity, a path to maturity, a turning-point moment, turning away from external structures to the very core of Christianity. Out of the theological and sociological crisis of modern Western Christianity (its noonday crisis) its members can seek the path to a deeper, more credible and mature form of church, theology and spirituality, its afternoon of Christianity.

While I have focused on the situation of the Catholic Church principally in Central and Eastern Europe, the operable question to be addressed is whether this analysis could also be useful to interpreting developments and needs in other parts in the world. The more global need is underscored by the findings of many contemporary sociologists who argue that the period of secularization is over, that “God is back,” and that we live now in a post-secular age. However, a number of key questions, all of which are critical to the discussions in this colloquium, include:

- Is the postmodern, global, pluralistic society truly post-secular?

- Is the contemporary return to religion a signal of an emerging new era of Christianity?

- If #2 (above) is true, which God “is back”? What type of religion has returned? Is the Christianity of the new era a “resurrected Christianity,” transformed as was the resurrected Christ? Should we expect another God?

An important question to be raised in this colloquium is whether the Christianity of this return to religion amounts to superficial emotional religion on the contemporary religious market or fundamentalism, a conservative nostalgia for pre-modern Christendom, militant religion, calling for crusades against modernity as the culture of death, or something else. An analysis of the Church suggests that three different types of the return to religion are occurring within Christianity. First, there is an increasing role of religion in politics. Second, there has been a “religious turn” in postmodern philosophy and a new concept of God in postmodern theology. Third, there is an increasing interest in spirituality. However, each of these types is subject to variations and nuances.

Secularization: A Divorce of Christianity from Religion?

We theologians should perhaps distinguish between secularization (the cultural revolution of the modern age) and secularism (the ideological interpretation of secularization). Secularization is neither the end of Christianity nor the end of religion. Rather it is the end of the Christian religion or Christianity as a religion. Secularization prompts a divorce of Christianity from religion. If we use the word religion in the sense of an integrating force in society (i.e. the thing that integrates society is its religion), then Christianity is no longer a religion, at least not in the religion of Europe; rather, it is assuming a new cultural form and role.

Historically, the West’s religion (in the sense of the integrating force and common language) proved to be science. Later, during the Romantic period, it was supplanted with culture, particularly art, then the nationalist cult of the nation, followed later by the political religions of the twentieth century. Today’s religion is most likely the capitalist economy, the mass media, and the market in information, with the latter being, perhaps, the principal commodity of our present age. In the West, the media fulfills a number of roles that were previously performed by historical religions, chiefly Christianity. Media interprets the world, offers common symbols and great narratives, and is the arbiter of truth and importance, influencing the way people think and live.

The post-Enlightenment period represents a critical change in the role and relevance of Western Christianity due to the decline of religion as the broad, integrative force of society. Western Christianity, divided between Catholic and Protestant views, was then also compelled to confront other religions in other parts of the world. In the course of the late modern era Christianity became one of the world views (Weltanschauungen) and has also sought to ensure its favorable acceptance within society. These developments cast Christianity into a unique role, as it were, confronting critical questions about itself and its relationship to daily life: (1) Was Christianity to be the guardian of a certain cultural tradition? (2) In its role, was it a source of expertise and wisdom on ethical issues? (3) Was it limited to being a spiritual source of religious experience? (4) Was it relegated to serving as an aesthetic accessory? (5) Was it to be shaped according to the political vision of the socially-oriented political left or the political ideology of the conservative right? (6) Was it to remain solely an institution for the social and charitable care of the poor, ill, and disabled?

It is important to note that secularization and the emergence of secular society are not the end of Christianity but rather represent an opportunity for the absorption of Christianity into modern culture and civilization. Christianity – the religion of the Incarnation – was actually almost always syncretic; it was incorporated into various cultures. There was always some earlier cultural and religious context that Christianity entered into, thus creating the different varieties of Christianity with their own specific spiritual, theological and liturgical differences. Absorption of Christianity in current society has become so thorough as to be virtually invisible. Many political ideals of the modern era, from the slogans of the French Revolution to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and hopes for a just future or a future society of abundance, are secularized forms of classical concepts of Christian theology. The modern age has gone much further towards fulfilling many Christian values and ideals (including Saint Paul’s appeals for an end to the barriers and inequalities between cultures, nations, sexes and social classes) than did Christendom, the Christian Europe of the Middle Ages. Secular culture contains far more Christianity than the protagonists of secular humanism are willing to admit, yet we are scarcely aware of the Christian nature of absorbed Christianity. The Christianity that we experience today is not pure – it is profoundly interfused with the secular culture of the West. The current nature of absorbed Christianity raises a critical question about next steps in modern society and whether there is a “via media,” or middle ground, between nostalgic traditionalism and cheap uncritical conformism with modernity. If so, what is it? Every change in civilization’s paradigms requires recontextualisation and this is generally a lengthy and dramatic process of seeking new forms and a new style. Christianity currently stands on the threshold of another of its historical metamorphoses.

The crisis of the Church affords the Church to look inward and to be self-reflective regarding its role and relevance in the modern world. The practical question of whether the Church reflected sufficiently on the questions prompted by modernity must also be taken up with some focus on the spiritual development of Christianity during this period of crisis: did the Church reflect also on “God’s hiddenness” within these developments and what were the calls to the faithful amid the changes caused by modernity? The Church’s encounter with the “Secular Age” has been a hard lesson but, in many ways, useful, offering the Church the opportunity to purify itself from triumphalism and to liberate theology and spirituality from a superficial concept of God. At its foundational level, contemporary Christianity must be prepared and honest when asking if it is ready to turn to the deeper understanding of the Christian faith.

The Return of Religion as Threat: Do We Need a New Political Theology as an Answer to Religious Fundamentalism and Extremism?

The return to religion in the modern period has, unfortunately, been accompanied by a dark side that includes fundamentalism, extremism, and terrorism. Modern Christianity must confront the causes of these phenomena as well as to develop strategies on how to overcome them. Ironically, religion in the modern period also provides the corrective to its dark side when it assumes its role as an instrument of peace and reconciliation. In many parts of the world, the Catholic Church played an important historical role in nonviolent transitions from authoritarian regimes to democracy. Yet, this process was, in many ways, left incomplete; after the fall of totalitarian regimes a process of reconciliation is critical in order to heal the deep wounds and divisions of the past and to foster the moral, spiritual and cultural recovery of the nation. Important agents of change at this stage include faith based communities.

Within modern society, the Catholic Church occupies a unique role as mediator in the ongoing, often-conflicted transitions and dialogue between the world of Islam and the secular West due to the many interests and ideas that it shares with both sides. However, the service as mediator in a modern dialogue is not undertaken by the Church without risk. The often contentious relationship between religion and politics has been understood for some time as having been resolved. The operable model today is one of “separation between church and state.” Yet, this model is contextual and its importance was generally applied at a time when the state exercised a monopoly over politics and the Church exercised its own monopoly over religion. That time has passed. The continuing process of globalization has created a new cultural context in which modern society has to reconceptualize the relationship between politics and religion. The Church must take up several critical questions, including: (1) Does contemporary political theology offer a competent analysis and an adequate response to recent changes to the political role of religion? and (2) Does modern society require a new political theology?

Return of Religion as Opportunity: Postmodern Philosophy and Theology for a Post-Secular Age

New intellectual impulses in postmodern thought have provoked many new questions worthy of further examination and analysis, especially questions that address philosophical and theological ideas and paradigms. The Church’s inquiry might begin most productively by first posing whether the religious turn in postmodern philosophy, from Levinas and Ricoeur to Luc Marion, Vattimo, Caputo and Kearney, is a sign of a transition from the secular age to a post-secular age, that is, its transition from its noonday crisis to the afternoon of Christianity. Subsequent questions about sources and methods follow and include: (1) Which “new concept of God” can offer a post-metaphysical style of thinking? (2) Can a “secular theology” (from Bonhoeffer to Vattimo) help the Church better understand the signs of the time (or are these dead ends for Christian theology)? (3) Is radical theology a proper antidote to secularism? (4) Does the “linguistic turn” in philosophy (Wittgenstein) and “analytical theology” support the renewal of religious language? and (5) Can the concept of “anatheism” – to believe again, after a secular crisis (Kearney) – serve as an inspirational impulse for deeper and more mature faith?

This relationship between ideas and change cannot be discounted. The reforms of Vatican II were the fruits of the new theology then emerging in France and Germany. In the modern period several additional considerations for the Church include what type of theology could support the reforms of Pope Francis and how academic theology could influence the faith and life of believers.

A Church for “Seekers”: The Need for Changes in Ecclesiology, Spirituality, and Pastoral Theology

Churches in the future may find themselves continuing to operate within an increasingly pluralistic cultural milieu and, as a result, characterized by greater internal pluralism. In the future we may find there are more ways of being a Christian than those with which we have become accustomed. (Casanova).

A principal social distinction in the West today is not the division of believers and nonbelievers but the division between dwellers, or parishioners, and seekers (Wutnow). Of concern to the Church is the development in the West whereby the number of dwellers is decreasing while the number of seekers is rapidly increasing. Even within these groups, though, some additional distinctions emerge and require explanation. Seekers among believers are those for whom faith is not a treasure of final truths, but rather a spiritual way while seekers among nonbelievers are “spiritual but not religious,” and seekers occupying a middle ground between believers and nonbelievers are simul fidelis et infidelis. Seekers are not fully identified with organized religion, with the teaching and regular practice of institutional churches. In this sense, these seekers may be thought of as “the new Zaccheuses.”

The two predominant morning-time activities of the Church have been targeted at dwellers. Traditional pastoral activity has typically focused inward, on the ranks of practicing believers and traditional missions have sought to broaden those ranks. One of the salient features of the afternoon of Christianity, in contrast to the morning of its history, will most likely be a greater detachment from existing institutional and doctrinal structures, and a concomitant emphasis on a third path for the Church’s action in addition to classical pastoral or missionary activity. That third path is accompanying seekers. This third path, focusing on seekers, does not consist of efforts to convert (unlike missionary activity) but to travel part of the journey together in dialogue. The principal goal of this accompaniment is not to push the seekers back into already existing structures of the Church but, through mutual dialogue, to enrich and to enlarge the existing structures so as to integrate the experiences in the treasure of faith. The greater understanding that ensues also enables the Church to open wide its treasures of spirituality to those who seek and in ways that are most relevant to the seekers’ journeys. (For example, in a period when spirituality is so popular, Christian mysticism offers a distinctive appeal to those who seek more profound spiritual relationships.)

The new theology of liberation should integrate not only the perspective of the socially marginalized, that is, people on the edge of society but also the perspective of people on the edge of the Church. As faith and doubt have a mutually dependent relationship, so, too, do seekers and dwellers need each other. In their well-known debate in Munich in 2004, Cardinal Ratzinger and Jürgen Habermas came to the conclusion that self-critical Christianity and self-critical secular humanism needed each other in order to rectify each other’s one-sidedness. The greater exchange between dwellers and seekers also serves the Church, enabling it to read the signs of the times with greater accuracy and nuance and better preparing the Church for the afternoon of Christianity.

If accompanying and dialogue are to be appreciated as a fully-fledged service to the Church, of equal value to missionary activity, this must presuppose a radical shift in ecclesiology. The church’s self-reflection in the future will most likely give rise to a broader concept of ecumenism and catholicity. With greater reflection and analysis, the Church enables itself to understand even better its full role and relevance in a complex and rapidly changing modern world. As noted by Orthodox theologian Evdokimov: “We know where the Church is, but we don't know where she isn’t.” As the Church confronts its current noontime crisis and contemplates its future, the need for this reexamination becomes manifest. The radical changes proposed here in ecclesiology as well as in spirituality and pastoral practice are necessary if the afternoon of Christianity is to be a productive time for the Church and Christianity in the West.